no more fun, plodding, carefulness, old rope…

‘It became green everywhere in the first spring, after London ended…’

Richard Jefferies, After London: Wild England, 1885

London is overwhelming. When making work, I can garden, tidy up and re-arrange. I self-soothe in doing so; I can serve my urge to pull legible patterns from the morass, try to find meaning in chaos. I’ve been interested in the less visible histories of London since living in a rectory in Poplar, an area that was full of revolutionary momentum at the beginning of the 20th century but has since been crumpled by bombings, urban planning disasters and capitalist greed. In reading Peter Ackroyd’s London (2012) and Bob Gilbert’s Ghost Trees (2019) and having lived in the city for most of my life, I am struck by its tendency to produce moments of the uncanny and inspire magical thinking. London is often eerie because of the lasagne of its architectural history, the collision of its cultures and the potential for intimate encounters with nature despite its highly constructed landscape.

I encountered the uncanny and absurd during my first period in residence at The Writers Room. A pigeon alighted on the toe of my shoe as I drank my morning coffee. From the bench outside the space, I saw a spider’s perfect web strung between two railings, backlit by the sun. Opposite, a crowd of snails were arranged, spiralling, around a rotting cherry stump in the wet shade. I ate my lunch in nearby Gibson Square and realised that the grand neo-classical building in the garden is a folly; it is a ventilation shaft, plastic bags trailing from its open grill roof. A man on the bus on my commute one morning drank a bottle of sherry whilst explaining the relationship between Christianity and Romani culture to a woman who hadn’t asked, and after alighting the bus violently assaulted a fibreglass cow.

I’m primarily a printmaker these days and am interested in the history of the craft in the hands of artists and industry, and how it has interacted with systems of power (religion, the state, pro-democratic movements) as a popular medium. Last year I came across the St Bride’s Foundation for the first time. It is a print workshop, theatre and archive conserving the typefaces and machinery of Fleet Street’s now defunct printing operations. In the print workshop hangs an idealistic poster, a 1932 monotype sample by Beatrice Warde which reads:

THIS IS A PRINTING OFFICE

CROSSROADS OF CIVILIZATION

REFUGE OF ALL THE ARTS

AGAINST THE RAVAGES OF TIME

ARMOURY OF FEARLESS TRUTH

AGAINST WHISPERING RUMOUR

INCESSANT TRUMPET OF TRADE

FROM THIS PLACE WORDS MAY FLY ABROAD

NOT TO PERISH ON WAVES OF SOUND

NOT TO VARY WITH THE WRITER’S HAND

BUT FIXED IN TIME HAVING BEEN VERIFIED IN PROOF

FRIEND YOU STAND ON SACRED GROUND

THIS IS A PRINTING OFFICE

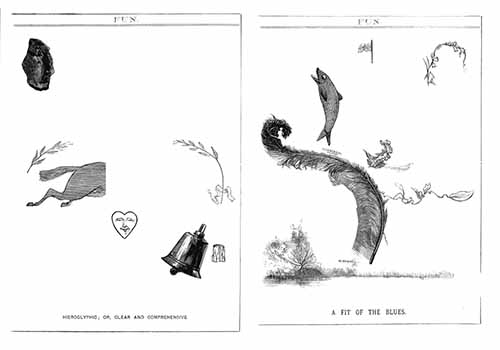

I’ve dissected a satirical annual called Fun (1876), which was published next door to St Bride’s at 80 Fleet Street and rearranged it into a short play or performance piece called No More Fun. Fun is akin to the better-known Punch magazine (1841-2002, founded by Henry Mayhew and wood-engraver Ebenezer Landells, published four doors down at 85 Fleet Street), filled with dense topical doggerel about goings-on in parliament and sneering, often racist articles about the colonies. Numbers 72-81 Fleet Street, formerly ‘Chronicle House’, is now demolished. I am using a 500-year-old medium (etching) to work with an old book made at a demolished building using an endangered craft (letterpress) to talk about the present.

My work comes from the perspective of a mad man, lecturer, soapbox preacher or amateur historian. I’ve used survival guides and doomsday pamphlets in the past, scooping them out to leave only an echoey, arch and pathetic rhetoric behind. No More Fun is a work in the voice of one of these characters. The character is a drunkard; ‘Toppin Bobbin’ is a melding of 16th century woodcutter and doomsday prophet Adam Toppin and 18th century engraver and satirist Tim Bobbin. During the first period of my residency at The Writer’s Room I was in depressive rut and spent time reflecting on the mental illness I encountered on the street, the tradition of ‘Raree-shows’ (purveyors of peep-show dioramas and esoterica) and the idea of the insightful ‘fool’ in Shakespeare and old satires (Punch & Judy, Somebody and Nobody). Madness in King Lear is framed as a powerful chaos: “His roguish madness / Allows itself to anything” (Act III Scene vi). In writing No More Fun I picked out a fourth-wall breaking phrase for my drunkard: “Why am I privileged to smash anything I please?”

I have realised that No More Fun is hauntological, referencing materials from the grubby past that seem to resonate in the toxic present, in response to what seems to be an ailing future. Print series like Marcellus Laroon’s Cries of London (1687) and the illustrations for Henry Mayhew’s London Labour and the London Poor (1851) represent those operating at the vulnerable margins (or literally dredging the sewers) of London life, even whilst it was the wealthiest city in the world. Rudolf Ackermann’s A Microcosm of London (1808-10, etchings by Thomas Rowlandson and Augustus Pugin) suggests a city of monuments and wonders. There is an absurd grandiosity and obvious futility in trying to reduce the city to a microcosm or system of archetypes, but my series of etchings to accompany No More Fun are intended as a series of hauntings – visual encounters possible in both present and past London. When making images, objects, and text from found material, I think I am a bottom-feeder, trying to extract nutrition from decaying mulch rather than addressing something shinier, more vital, and contemporary.

‘Of the Dredgers, or River Finders, of the Sewer-Hunters, the Mud Larks…

In remote days, everything connected… the tide… and the nature of the bottom…

valuables among the rubbish… Bones, and old rope… mixed with some hoped-for prize.

A living as it were by a game of chance… plodding, carefulness… tattered, indescribable things… hunger in the mud…’

(Lines lifted from Mayhew’s London Labour and the London Poor, 1851)

*

The following are images from No More Fun accompanied by a text pieced together from ‘Punch’ during my first stint in The Writers Room.

[A man, Toppin Bobbin, walks into a bar, snail trails or rain shining from the shoulders of his coat. He is in disarray and begins to speak a kind of incantation]

“Stand about, and watch a man gesticulate and shout,

I am that merry wanderer, full of spite.”

[After removing his crush-hat in an easy manner, and winking airily at the orchestra, he will begin, like a dustman crying out for dust]

“I have a right to take my material from any source that may seem good to me, born with a propensity for illicit jam.”

[He proceeds to smear himself hideously with jam]

“When I am gone, lay me in a plain white jelly-pot. We eat marmalade, but we know not what it is made of…From the subterranean regions I conjure up a recollection from my skull, in flail-like phrase.

Ditchwater is an effervescing beverage – I drink your very very good health!

[He drinks the dregs of an abandoned pint]

A scent of risk, a whiff of blood dropping, drifting in mid-air

Wing-flappings and incidental beak-proddings - see how they cluster, crush and clatter.

I’m supposed to be fishing but haven’t done much yet, innovations of the modern muddle - if a nutshell may be considered as a hat.

Wavelets lap and bubble, the whirligig of time, apathetic or languidly amused? Awkward gear.

Just been bitten by a strange dog! When I come to think of it.

Heaps of money in this strange world of gilt and garish light.”

[Soft was his speech now, as muffled by some atmosphere surcharged with snow]

“How deftly spreads his sludge - a net to catch the moonbeams, visions of the apocalypse of self. Pleasant dream! Pleasant dream!”

[Suddenly carried away by histrionic enthusiasm, he brings his fist down violently on the precise spot where a table ought to be, but is not, standing. He hits himself with force, hurts himself considerably and is furious]

“The fragrant smoke cloud, the foaming cup.

Pocket the dust, man of stout, like a cornered rat in a big pit!

The severe stonework frowns, composed of slate and slime.

The mystic letters in your innermost recesses -

Fragments of newspaper concealed in stale buns;

The thin sweet sound of stricken strings

In the bland buzz of cultured chat,

An unscientific dialogue on a highly uninteresting topic.

That was vile, that was vile,

A trifle vague perhaps, in composition -

How bad my head must be to make this?

I’ll chase my fears, like foxes in these hot days of hurry,

They with snips and snaps and snarls –

Howlings and whinings, yelpings.

London in mid-winter, that huge and awful tract of forest.”